The Żabiniec creek valley in Szczecin

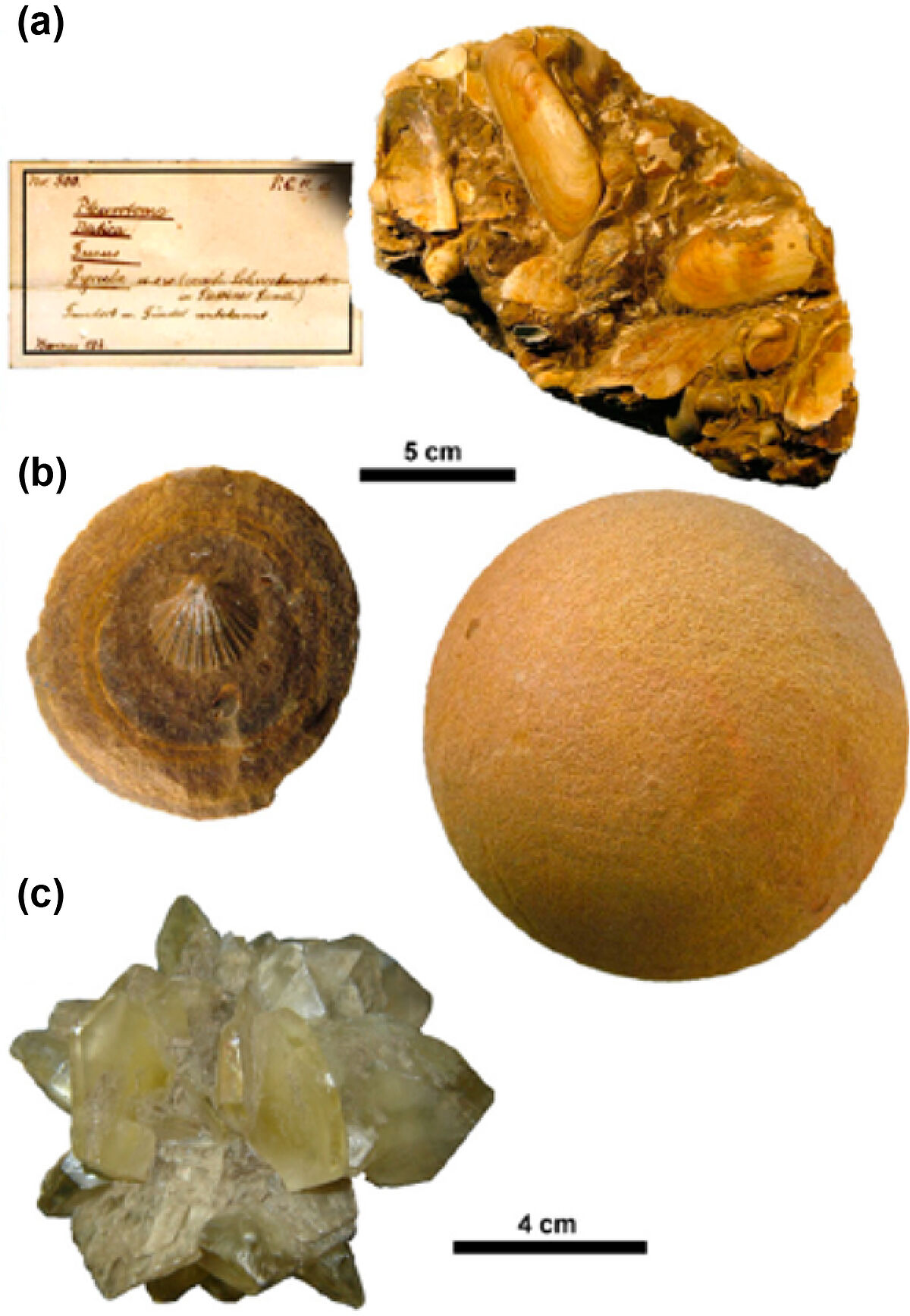

"Not everything that glitters is gold." – This also applies to the fossil of a butterfly, which was found in one of the "Szczecin Spheres" famous for Szczecin.

Ansorge (2015) uncovered this mystery and found out that it was a fake. A recent butterfly was mounted on the concretion using plaster matrix. First of all, this ball of sand provides no conservation potential for insects at all. Ansorge (1997) already expressed doubts about the find, but due to the unknown location of this find it was not possible to examine it more closely. Only a few years later the same piece turned up again at a fossil collector (Ansorge 2015).

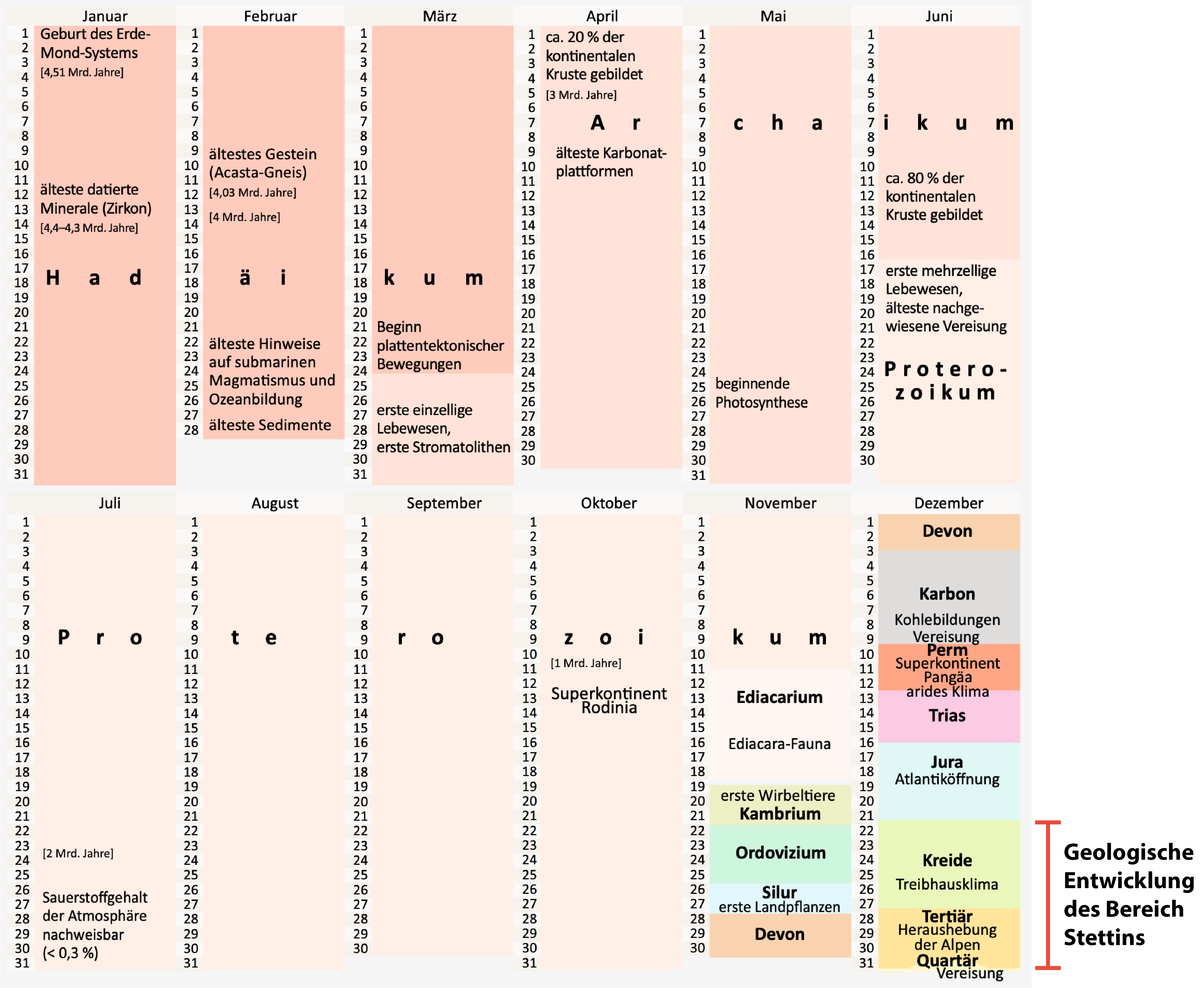

Prussian geologists first described the geological conditions of western Pomerania at the beginning of the 19th century. The Polish city of Szczecin is geologically located within the Cretaceous, Paleogene, Neogene and Quaternary (Maciag, 2020). That is a period covering up to 100 million years. However, compared to the age of the Moon-Earth system, it is a relatively short moment (Fig. 1).

Due to thick sequences of Pleistocene and Holocene sediments at the surface and near the surface (Fig. 2), there are no in situ outcrops of pre-Quaternary units around Szczecin (Borówka, 2013). Tills (rocks of various sizes transported by glaciers), fluvial sands and organic sediments represent the Quaternary layers. However, there are outcrops with Oligocene deposits (Tertiary). These sediments comprise iron concretions, which contain marine fauna (Fig. 3a). In addition, the so-called "Szczecin spheres" were discovered, spherically shaped nodules (Maciag, 2020; Fig. 3b). The Oligocene units contain many fossils, such as foraminifera, radiolarians, mollusks, shark teeth and, in particular, gypsum crystals (Fig. 3c) (Cedro, 1993; Cedro et al., 1995). In addition to slightly calcified clays, silt and sand, Paleogene sediments of the Oligocene also contain gypsum crystals and glauconite (Piotrowski et al., 2010). The thickness of these sediments sometimes reaches a few tens of meters. The Pleistocene deposits contain clay, whereas the Holocene deposits contain sand and organic soils in addition to clay (Piotrowski et al., 2010).

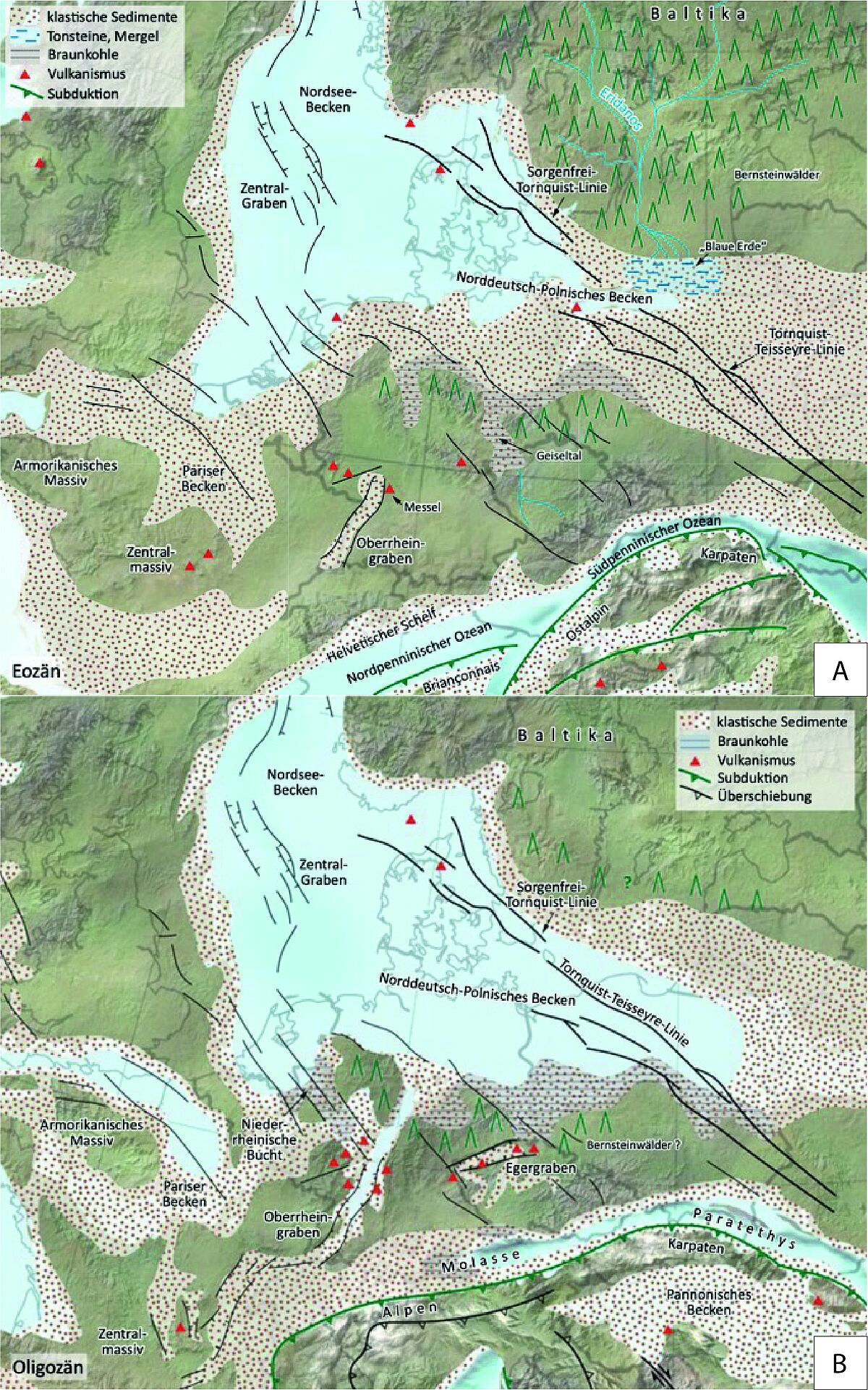

Typical of the Tertiary period was the development of subsidence areas (such as the North German-Polish Basin) (Fig. 4). The formation of a shallow marginal sea resulted in the deposition of sandy and clayey sediments in northern Central Europe. A large number of lignite seams formed, which were covered by thick quaternary deposits (Meschede, 2018). During the Pleistocene glaciation phases in the Quaternary, large terminal moraines (sometimes glacitectonic complexes) were "piled up" by the thrust of the glaciers. As in the area of the Muskau Arch in the border triangle of Brandenburg-Saxony-Poland, some of the Tertiary lignite seams occur near the surface along the border between Germany and Poland.

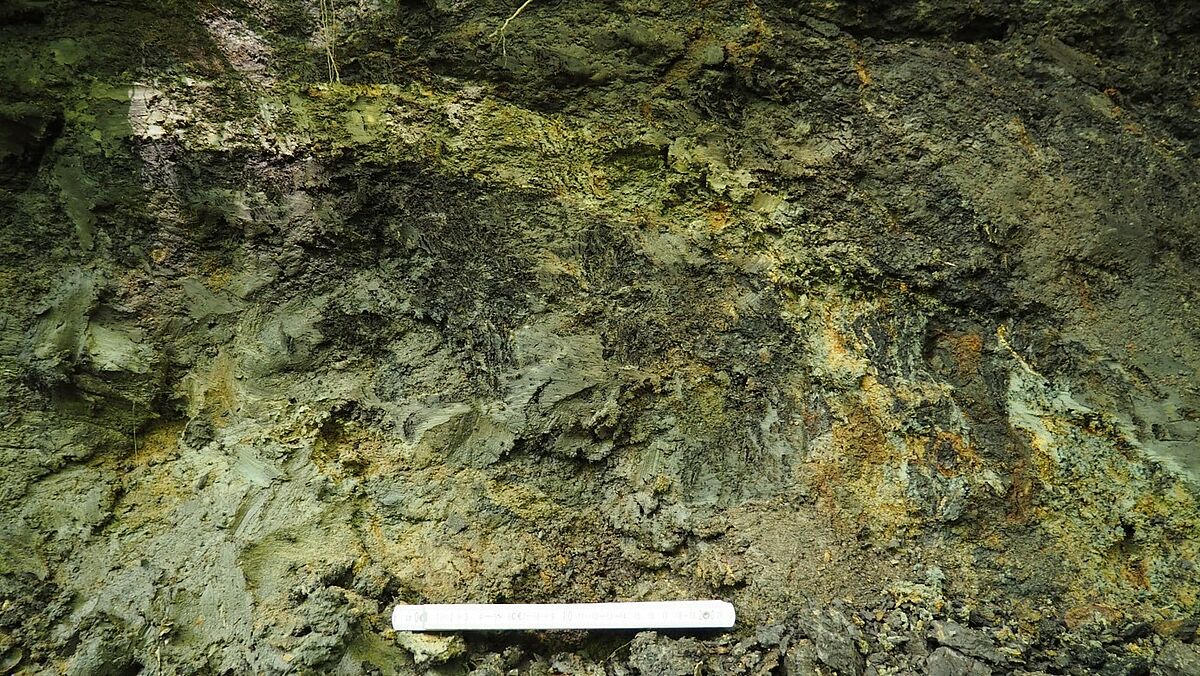

The valley of the Żabiniec creek is located in the northern part of the Szczecin City Forest, which adjoins the Ueckermünde Heath. The hill present here is part of the Warszewskie hills and belongs to a terminal moraine, which may have been formed by glaciation in the Saale complex. The Żabiniec creek valley cuts into these sedimentary sequences and thus provides a view of the interior of the terminal moraines. Tertiary clays (Figs. 5 and 6) were raised by the glacier-related shearing processes in the subsoil, which are also exposed at the creek. This is a geological feature in the north of Szczecin. Meltwater gravel and sand (Fig. 7), which are covered by loess units, originate from the Vistula glaciation.

The particularly severe erosion in this creek is spectacular compared to the surrounding creeks and results from the water being diverted into this area. This is why such excellent outcrop conditions can be found here.

References

[Translate to English:]

Ansorge, J. (1997): Insekten in Geschieben. Überblick über den Kenntnisstand und

Beschreibung von Neufunden. – Berliner Beiträge zur Geschiebeforschung, 113-126, 6 Abb., 2 Taf., Dresden (CPress).

Ansorge, J. (2015): Günther Wangrins Tagfalter–Versteinerung in einer Stettiner Kugel – die Geschichte einer Fälschung. Geschiebekunde aktuell 31 (4): 98-103, 2 Taf., Hamburg/Greifswald.

Borówka, R.K. (2013): Budowa geologiczna i rozwój rze´zby Pomorza Zachodniego. In ´ Srodowisko Przyrodnicze Wybrze˙zy Zatoki Pomorskiej i Zalewu Szczeci ´ nskiego; Borówka, R.K., Musielak, S., Eds.; Oficyna In Plus: Szczecin, Poland; pp. 5–18.

Cedro, B. (1993): Wyst˛epowanie mineralizacji siarczanowej w iłach trzeciorz˛edowych okolic Szczecina. Wszech´swiat, 12, 304–308.

Cedro, B., Lorenc, S., Zimmerle, W. (1995): Zur Petrographie des oligozänen Septarien-Tons im Raum Stettin (Szczecin). Zentralblatt Geol. Paläontologie, 1, 147–159.

Maciag, L. (2020): Practical Toponymics: Szczecin on the Geographical Map of World. Geosciences, 10, 37.

Meschede (2018): Geologie Deutschlands. Ein prozessorientierter Ansatz. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Piotrowski, A., Rielsko-Rybak, J. Sydor, P. (2010): “Szczecin on stilts” - geological and engineering conditions of the foundation of the city and port in the Oder Valley. In Proceedings of the LXXX Scientific Congress of the Polish Geological Society, Szczecin, Poland, 11–14 August 2010. (In Polish)

Zygmunt, M., Cacón, S., Milczarek, W., Sanecki, J., Piotrowski, A., Stepień, G. (2020): The Three-Segment Control and Measurement of Reliable Monitoring of the Deformation of the Rock Mass Surface and Engineering Structures on the Miedzyodrze Islands in Szczecin, NW Poland. Geosciences, 10, 179.