The big stone of Altentreptow

Please note: Once you watch the video, data will be transmitted to Youtube/Google. For more information, see Google Privacy.

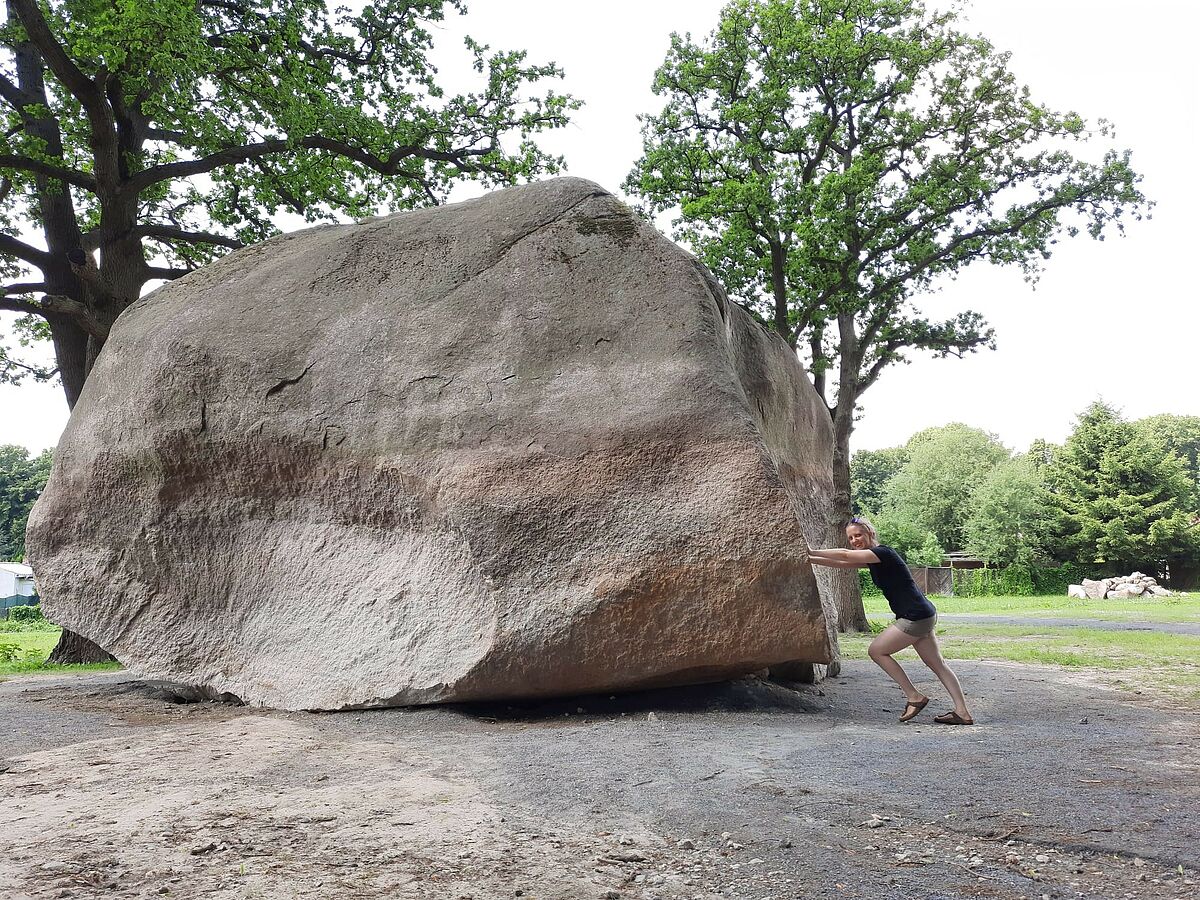

The "Big Stone" (Fig. 1) is an erratic boulder at the Klosterberg in Altentreptow. Numerous legends are entwined around its history. In one of these stories, the stone is evidence of a competition:

“Two giants once lived on the border between Neubrandenburg and Treptow, a Mecklenburgian and a Pomeranian. One day the two agreed to throw two large stones in a competition. The Mecklenburgian should aim his stone at the Treptow church tower, the Pomeranian tried to hit the church tower of St. Mary´s Church in Neubrandenburg. When it came to throwing, both giants missed their target. The Pomeranian giant's stone flew about half a mile over Neubrandenburg and landed near a paper mill. He bears the name "King of the Centuries". The Mecklenburgian hit better than the Pomeranian: his stone just missed the Treptow church and hit the Klosterberg. It still lies there today as the Big Stone of Altentreptow.”

In another story, the devil himself threw the stone at the church tower and also missed it. Today we know that the Great Stone was not thrown into place, but ice movement played a central role. Geologists refer to rocks that have been transported by glaciers as erratic boulders. In the size of the "Big Stone" one also speaks of erratic boulders. With a volume of 166 m3 and a weight of 450 t, the Big Stone is the third largest erratic boulder on the north German mainland. The largest erratic boulder is the Buskam. It juts out of the Baltic Sea about 300 m from the coast of Rügen. Its total volume is about 206 m3 (Obst 2004).

The Big Stone is also known as the "Bismarck Stone" because the boulder was once decorated with an inscription in honor of the politician. The inscription was carved on April 1, 1915 and removed again in 1959. Today the remains of the engraving have practically disappeared.

In May 2021, the Big Stone moved into the limelight when, after years of discussion, a lifting of the 450 t boulder was initiated (Fig. 2). Since then, the Big Stone can be viewed in all its splendor, measured and now also watched as a digital 3D model.

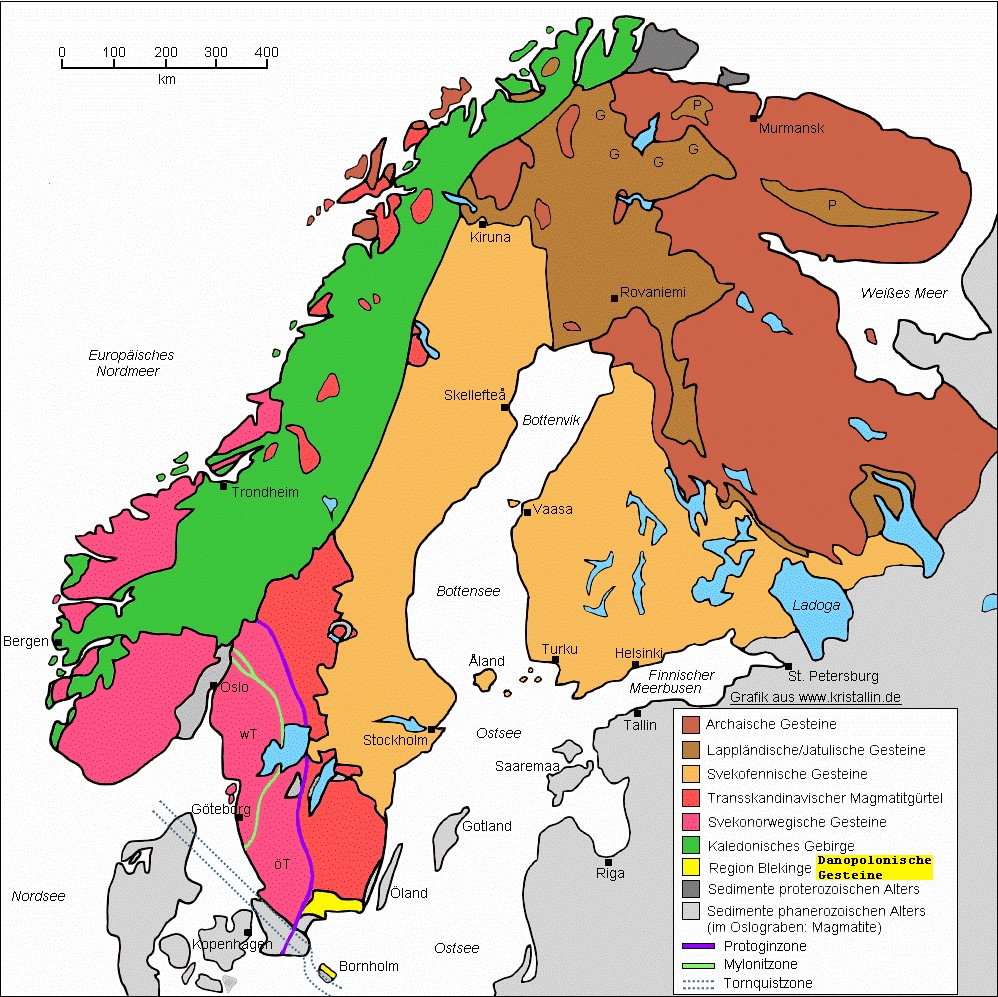

For a long time it was assumed that the Big Stone was Hammer granite from the Hammeren region on the Island of Bornholm. Hammer granite is characterized by individual dark biotite aggregates and a red color distributed across the grain boundaries (Wilske 2019). Based on a closer examination of the Big Stone in 2021, it becomes clear that the rock properties of the Hammer granite do not apply to it. The granite is very uniform and homogeneous in color (Dr. Karsten Obst, LUNG M-V, pers. comm.). This makes it more similar to the Spinkamåla-type Blekinge granite. This granite is named after its region of origin, Blekinge in south-eastern Sweden (Fig. 3). It was formed there around 1.4 to 1.5 billion years ago during the Danopolonian orogeny, when magma rose in the earth's crust and slowly solidified there (Dr. Karsten Obst, LUNG M-V, pers. comm.).

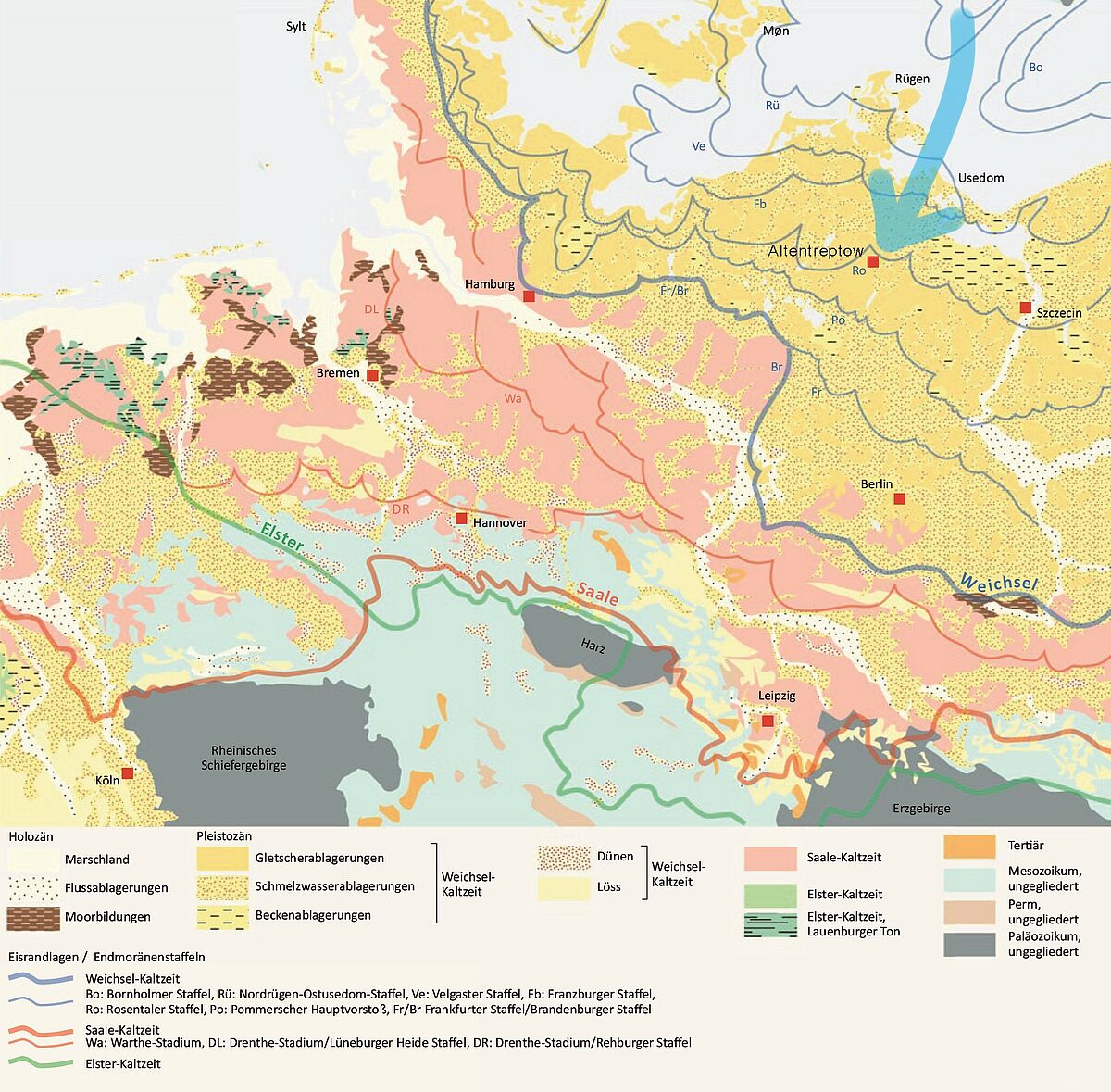

The glaciers of the most recent glaciation in Northern Germany (Weichselian Glacial) detached the boulder from the rock structure and transported it in the direction of Altentreptow, 300 km away (Fig. 4).

For those who are particularly interested

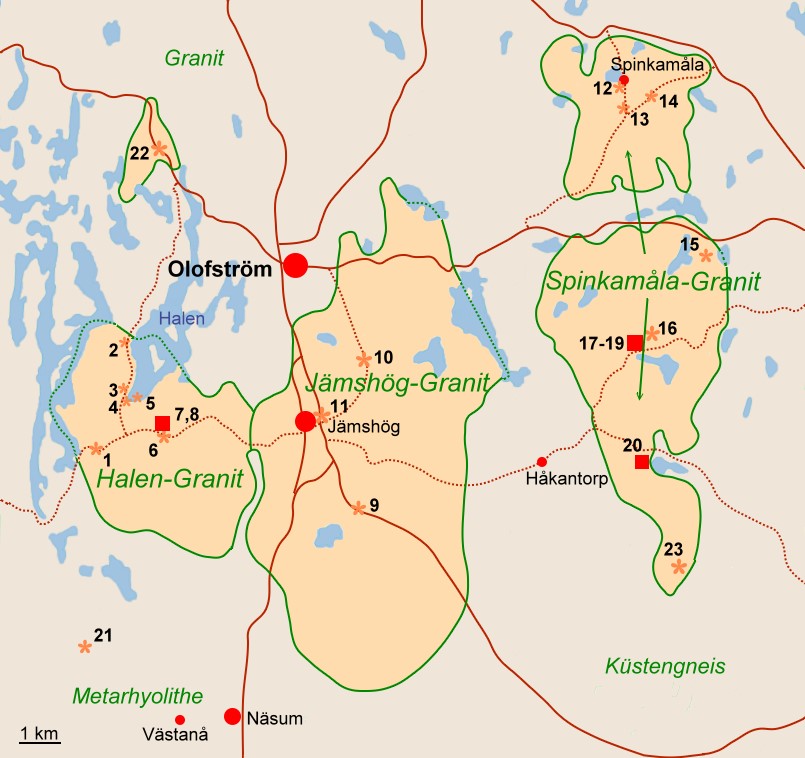

The special granite type of Spinkamåla was named by Holst and Kjellström in 1897 after the small town of Spinkamåla, north-east of Olofström (Fig. 5). The fine to medium-grained granite (Fig. 6) can be found in small and large massifs. In addition to its variety of colors from gray to almost reddish, it can also be found as dike rock in older granitoids. (Wilske 2018).

Zandstra (1988) described the Spinkamåla granite as a fine-grained rock west and north-west of the AusführungKarlshamm granite massif. In contrast to the Karlshamm granite, the Spinkamåla granite has no hornblende. The uniform grain size and the irregular grain boundaries are also characteristic. The feldspars are usually formed as Carlsbad twins and have an average size of 6-8 mm. These gray or reddish-brown microclines are usually explicitly oriented and follow clearly recognizable tracks. But this rock is also available in a directionless and uniformly grained variant. This is characterized by a lack of biotite and a matrix dominated by quartz. The quartz can appear gray to blue. In summary, the Spinkamåla granite is a quartz-feldspar-biotite rock.

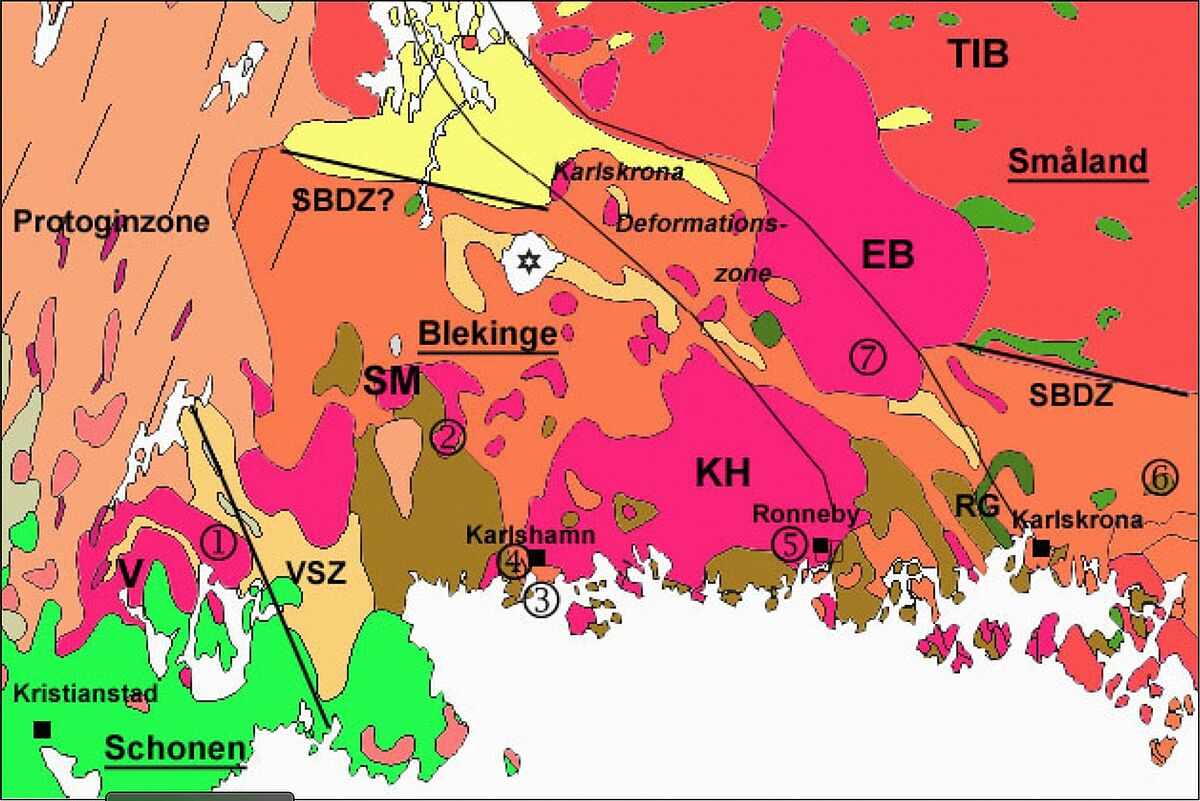

There is a genetic connection to the Blekinge granite (Norin 1936). The region around Blekinge is bordered in the north by the Småland granites and the porphyries of the TIB (Trans-Scandinavian Magmatic Belt) (Fig. 7, Krauss et al. 1996; Lindh et al. 2001), in the southwest by the gneisses of the east segment and in the west by the Protogin zone (system of zones of deformation and weakness). The Karlskrona deformation zone runs between the Karlskrona and Eringsboda granite (Altenburg 2011).

About 1.77-1.75 billion years ago the bedrock of the Blekinge region was formed (Johannson et al. 2006). Due to later uplift, today's highly deformed Blekinge rocks reached the area next to the almost undeformed Småland granitoids. The Karlshamm and Eringsboda granites, which intruded into the region around Blekinge (Altenburg 2011), are much younger with an age of about 1.45 billion years.

Due to the unremarkable appearance of the Spinkamåla granite, it is rarely found, but represents an indicator stone. It is usually compared to the Halen granite (Altenburg 2011). However, since the Spinkamåla granite is usually only finer-grained, no strong distinction is made between the two. It is assumed that the Spinkamåla-like rocks come from the same magma chamber, as do the Eringsboda and Karlshamm granites, two large massifs between which the Spinkamåla granites occur (Altenburg 2011).

References

[Translate to English:]

Altenburg, H.-J. (2011): Die Blekinge-Region – Gesteine im Anstehenden und als Geschiebe.Geozon Science Media 11: 19–28. doi.org/10.3285/ngb.11.04

Börner, A. (2012): Mecklenburgische Eiszeitlandschaft, Wiebelsheim: Quelle & Meyer.

Bräunlich, M. (2006): „https://www.kristallin.de/,“ www.kristallin.de/berg.htm. [Zugriff am 23 November 2021].

Buddenbohm, A. (2021): „Eiszeitroute - Infotafel,“ Altentreptow.

Callisen, K. (1932): „Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Granitgrundgebirges von Bornholm,“ C.A. Reitzels forlag, Copenhagen.

Ehlers, J., Grube, A., Stephan, H.-J., Wansa, S. (2011): „Pleistocene Glaciations of North Germany— New Results,“ in Developments in Quaternary Sciences, Elsevier, p. 149–162.

Johansson, Å., Bogdanova, S. & Čečeys, A. (2006): A revised geochronology for the Blekinge Province, southern Sweden. GFF 128(4): 282–302.

Krauss, M., Franz, K.-M., Hammer, J. & Lindh, A. (1996): Zur Geologie der Småland-BlekingeStörungszone (SE-Schweden). Zeitschrift für geologische Wissenschaften 24: 273–282.

Lindh, A., Krauss, M. & Franz, K.-M. (2001): Interpreting the Småland-Blekinge Deformation Zone from chemical and structural data. GFF 123: 181–191.

Meschede, M. (2018): Geologie Deutschlands. Ein prozessorientierter Ansatz. Springer-Spektrum, Berlin-Heidelberg.

Norin, R. (1936): Contributions to the geology of western Blekinge. Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar 58(4): 481–561.

Obst, K. (2004): „Veröffentlichung,“ Ostseezeitung, Bd. 219/52.

Wilske, H. (2019): „www.skan-kristallin.de,“ skankristallin.de/bornholm/gesteine/gesteinsdarstellung/hammer/hammertext.html. [Zugriff am 23 November 2021].

Zandstra, J. G. (1988): Noordelijke kristallijne gidsgesteenten. E. J. Brill, 339 pp.